The Long Betrayal

Words: Tom Reed

Football has priced out the poor people from the game that nurtured it.

The 1992-93 season, some 30 years ago, was a nondescript one for unfashionable Fulham.

The Whites were dumped out of the FA and League Cups in Round 1 by Northampton Town and Brentford respectively.

In goal, was the stout but fallible Jim Stannard, in midfield, the Kellys Mark and Paul struggled to make an impression, while forwards Peter Baah and Kelly Haag, despite sounding like soft-porn stars couldn’t score enough to secure more than a 12th placed finish in League Division Two.

Averages attendances topped out at 4,716 at Craven Cottage in the league, where a ticket for the Brighton match in the Stevenage Road stand would have set you back £2.50.

Fast forward to 2023 and the Fulham Supporters’ Trust are about to hold a protest against ticket price rises that are "alienating a large part of our core fan base”.

To understand why Fulham supporters, not particularly known for their militancy, are holding a protest march vs Manchester United, where tickets are being sold for as much as £160 each, we have to look at some context, so settle into your seat, make yourself a prawn sandwich.

Football is nothing without its textures, from the mud clagging between your studs to the paper of a ticket gripped between expectant fingers.

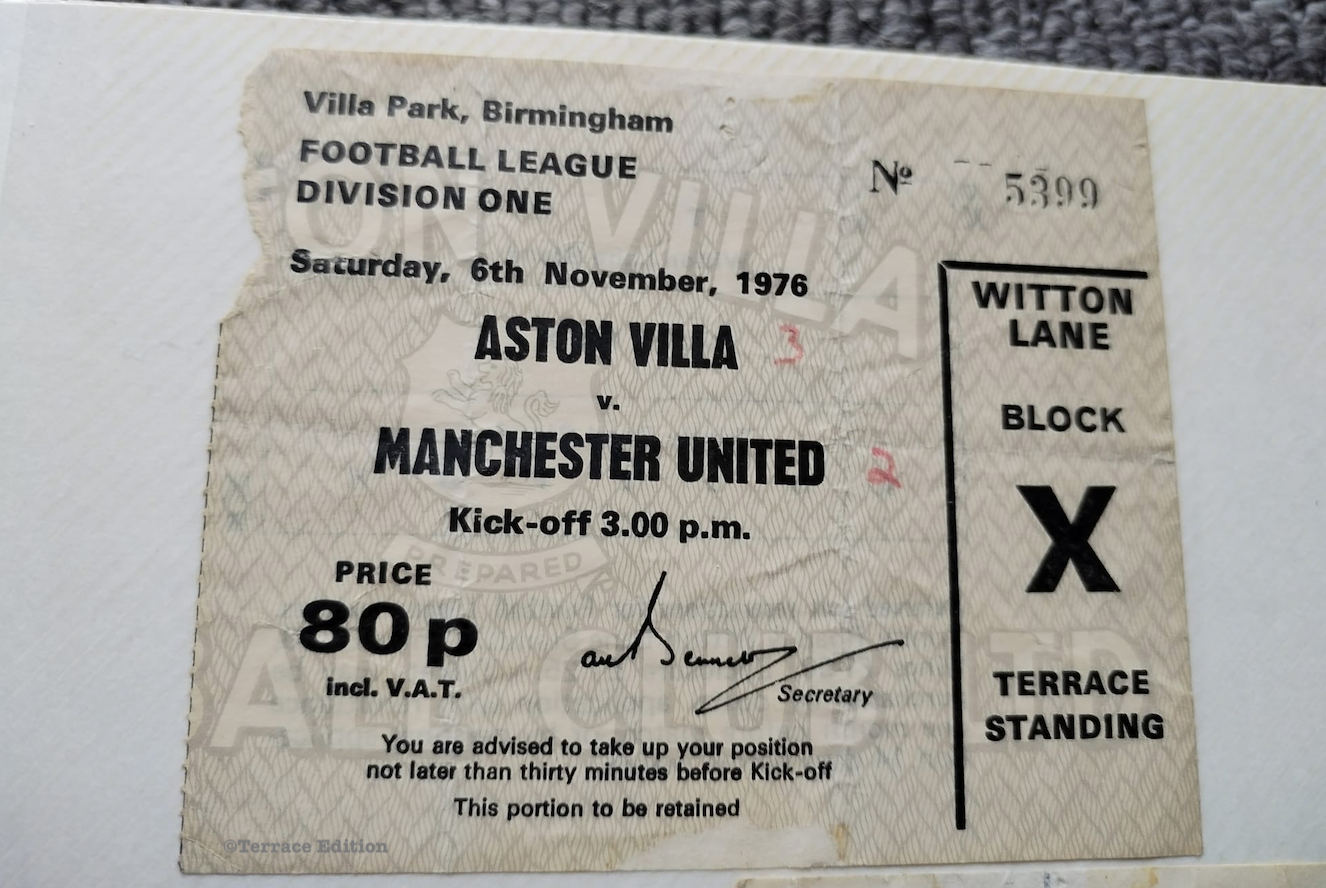

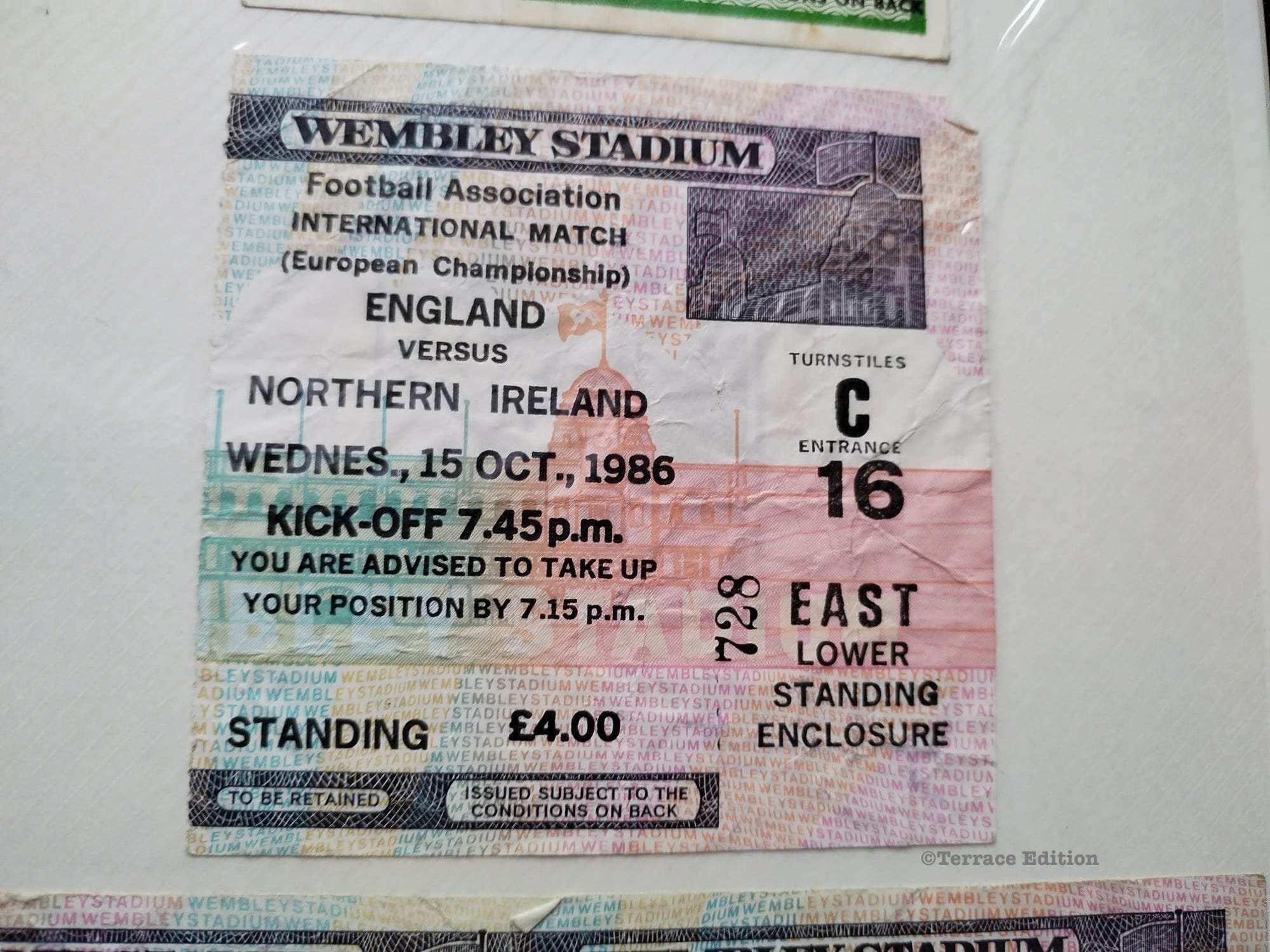

Fortunately, people have saved ticket stubs from the time before the Premier League revolution of the 92/93 season, that some call a coup, where Fulham could only dream of top flight and top prices.

A ticket from the Manchester United vs Liverpool derby from Saturday, October 1, 1977 is priced up at a princely 80p. Adjusted for inflation, using the Bank Of England calculator, a ticket for the same match in 2023 should come in at £5.61.

Anyone with any passing interest in Utd or Liverpool would know that a choice between finding a ticket for United-Liverpool for £5.61 these days or baring their arses in the Arndale Centre window would result in pink cheeks pressed against glass and distressed shoppers running past Pandora.

Other ticket stubs show a similar story, with an away ticket for Aston Villa vs Manchester United in 1977 chalked up at 80p, and the FA Charity Shield at Wembley going for £1.50, which would come in at under a tenner in 2023

©Nigel Bishop/ Terrace Edition.

Even by 1986, you could stand at Wembley for an international with Northern Ireland for £4.00, which translates to £11.42 in today’s money.

We could bang on about the working class and poor folk of England being locked out of a game they kept going through less fashionable times but sometimes a photo can say a thousand words.

Ian S.P. Reid’s photos of Manchester United and Manchester City in the year before the ticket stub, shows football as it was, a just about accessible folk event, where people without a pot to piss in, were able to build a terrace culture which was second to none.

The humble donkey jacket, a terrace staple across the seventies and various subcultures from greaser to skinhead, originated in Manchester, where it was originally worn by the operators of the donkey winch on the city’s ship canal.

Post 70’s, we began to see football’s second enclosure, the first being when club owners roped off sports pitches and began to charge for entry way back in the 19th century, the second enclosure coming in the late 80’s and early 90’s when the poorer type of fans were being written out of the sport.

Supporters that could jib in or borrow a couple of quid in the pub to get through the turnstiles, slowly found themselves out in the road, bustled by tourists and Audi drivers.

The Football Association’s Blueprint for the Future of the Football 1991 is about a clear example you need as to the attitudes of the game’s guardians towards the market that football would target.

“The implication is that hard choices have to be made as to the consumer segment to which the offer is to be targeted and hence the ingredients of that offer. As implied above, the response of most sectors have been to move upmarket so as to follow the affluent ‘middle class’ consumer. We strongly suggest that there is a message in this for football, and particularly in the design of stadia for the future”.

Of course, the Football Association helped create the Premier League in 1992 before promptly losing control of it, sending shockwaves across the global game and a free market-mania which has seen working class and poor fans shifted out of stadia across the world.

That takes us back to Fulham in 1992, the nondescript but proud West London outfit whose fans couldn’t have foreseen £3000 season tickets in a new Riverside stand and £160 individual seats for the visit of Manchester United on November 4.

It’s said that when a goal goes in at Fulham now, the seats bolted on to the Hammersmith End shudder and its a cruel irony that Craven Cottage retains reminders of the days when it wasn’t a financial worry to get in to matches, it’s just that fans without the means to shoulder the £71 walk up tickets for the upcoming match vs Sheffield United may have shuffled away quietly.

The English are very good at hiding poverty and with research showing that 3.8 million people experienced financial destitution last year in the UK, including 1.04 million children, it stands to reason that Fulham Supporters Trust are asking the club to love up to it’s “Fulham For All” for inclusivity pledge.

Indeed, while supporters at Craven Cottage are saying it can’t just be Fulham for all that can afford it, it’s important to note that expensive ticket pricing is not just a Premier League problem.

If we cast our eyes to Northampton Town, Fulham’s FA Cup vanquishers in 1992, with a team containing Terry Angus, who went on to play for the Whites, the cheapest adult ticket is £25 for tonight’s League 1 match with Leyton Orient.

It’s not unusual to see £20 plus asked of in non-League either.

Of course, lower league teams often post seasonal losses, are more reliant on gate incomes and do their best to offer reasonable season tickets, but their fans are still exposed to so called “price elasticity” which tests household incomes.

Over in Italy, AC Milan supporters produced a display recently reading “cap the away ticket prices” in reaction to a creep in the cost of travelling to catch the calcio.

Meanwhile, in Germany, known for its progressive fan policies, Fortuna Düsseldorf are turning the ticket price issue on its head by holding matches where all general admission tickets are free.

Last weekend, they held a full to the rafters trial match against 1. FC Kaiserslautern in Bundesliga 2 in which both home and away general admission tickets came gratis.

The “Fortuna For All” scheme is subsidised by sponsorship from companies, which may open up its own problems but there’s no doubting that it has sent a volley into the expensive seats in the debate over ticket pricing, putting further spotlight on the likes of Fulham and their £160 seats.

If a living wage is considered functional for a healthy society, then why not a living football ticket price for those that live in and contribute to to communities which clubs exist?

The Covid 19 pandemic showed once and for all that football without fans is nothing, with its ghostly stands and finally, supporters are waking up to the dysfunction of paying through the nose for a business which won’t exist without them.

The football industry should own up to the long betrayal of the poor and begin to make space for those working class and hard up fans, who often have both in common, to return, in numbers and without stress.

Those 70’s supporters from the photos in their butchers coats and their descendants and their spirit that made the game.

©Nigel Bishop/ Terrace Edition.

©Nigel Bishop/ Terrace Edition.

©Nigel Bishop/ Terrace Edition.

Tom Reed is Terrace Edition Editor and can be found on Twitter: @tomreedwriting